Yesterday we looked at the London Slutwalk. Today we continue our exploration of Mary Wollstonecraft's attitude towards modesty, from the chapter of that title in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

|

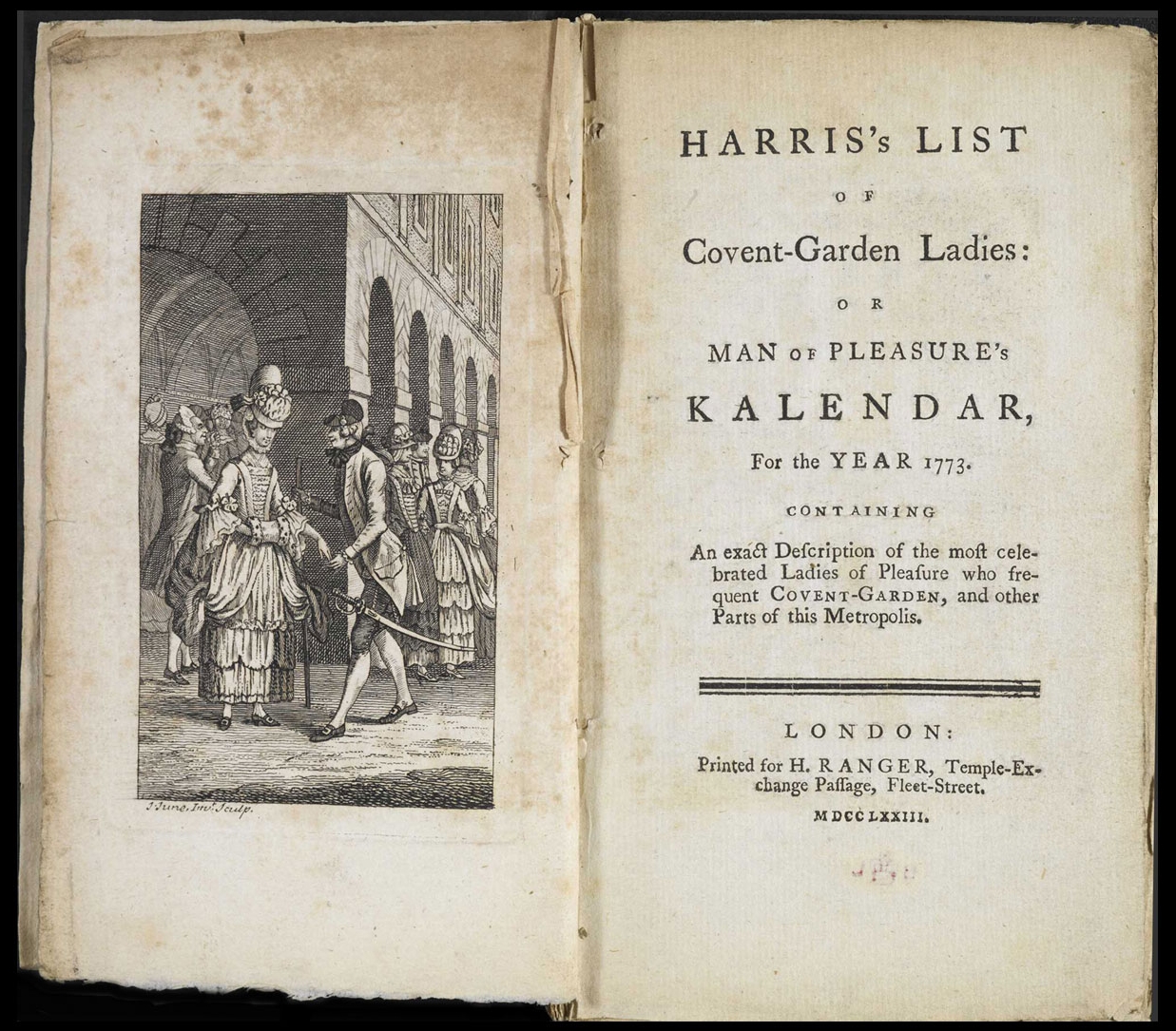

| By Samuel Derrick [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons |

She deals explicitly with prostitution, showing she is not a prude or someone with her head in the sand. The world's oldest profession had a huge impact on urban life at that time, not least because other occupations were closed to women. Dan Cruikshank claims in The Secret History of Georgian London: How the Wages of Sin Shaped the Capital that "as many as one in five young women were prostitutes in eighteenth-century London".

I am not sure of the scope of the term "prostitute" in her day. Mary, nobody's fool, would have been aware of the aristocrats' mistresses (predecessors of the pretty horse-breakers of Rotten Row), and Harris's List of Covent Garden Ladies : in other words, both those women seeking a long-term arrangement, and those who charged by the hour. Dr Johnson's Scottish companion describes his lusty London encounters in his diaries -- "I got myself quite intoxicated, went to a Bawdy-house and past a whole night in the arms of a Whore. She indeed was a fine strong spirited Girl, a Whore worthy of Boswell if Boswell must have a whore". James was carousing in the streets and the decades when Mary was a young woman.

She, and others like her, would have had to exercise an effort to minimise her risk of being approached or addressed as a street tart. Whether this effort was conscious or not, women had to perform goodness, or "virtue" in the limited female sense: hair, clothes, body language, chastity of the eyes, pace, voice, deportment, all signalled "don't mess with me", as opposed to "might be worth a try". "If you want to stay safe, don't dress like a slut," said the policeman very recently. When so many women were reduced to opening their legs for a few pennies, and the sexual scale went up from there, all "good" women who did not want to participate in those transactions had to take action to distance themselves from the "bad" ones. This was especially true for girls, that is, unmarried women. "If you don't want to be approached, don't give a man any reason to approach you." For a young woman walking the streets of London without a male escort, as Mary did of necessity, every signal she sent out was subject to scrutiny.

I am not sure of the scope of the term "prostitute" in her day. Mary, nobody's fool, would have been aware of the aristocrats' mistresses (predecessors of the pretty horse-breakers of Rotten Row), and Harris's List of Covent Garden Ladies : in other words, both those women seeking a long-term arrangement, and those who charged by the hour. Dr Johnson's Scottish companion describes his lusty London encounters in his diaries -- "I got myself quite intoxicated, went to a Bawdy-house and past a whole night in the arms of a Whore. She indeed was a fine strong spirited Girl, a Whore worthy of Boswell if Boswell must have a whore". James was carousing in the streets and the decades when Mary was a young woman.

She, and others like her, would have had to exercise an effort to minimise her risk of being approached or addressed as a street tart. Whether this effort was conscious or not, women had to perform goodness, or "virtue" in the limited female sense: hair, clothes, body language, chastity of the eyes, pace, voice, deportment, all signalled "don't mess with me", as opposed to "might be worth a try". "If you want to stay safe, don't dress like a slut," said the policeman very recently. When so many women were reduced to opening their legs for a few pennies, and the sexual scale went up from there, all "good" women who did not want to participate in those transactions had to take action to distance themselves from the "bad" ones. This was especially true for girls, that is, unmarried women. "If you don't want to be approached, don't give a man any reason to approach you." For a young woman walking the streets of London without a male escort, as Mary did of necessity, every signal she sent out was subject to scrutiny.

The following passage seems to refer to street prostitution. One wing of this was characterised by country maids being deceived on coming to the city (which still happens today, only the maids come from countries further afield and are often hampered by a lack of the local language). Mary Wollstonecraft characterises them as simple people who never had any real and elevating modesty to lose:

The shameless behaviour of the prostitutes, who infest the streets of London, raising alternate emotions of pity and disgust, may serve to illustrate [the difference between bashfulness and modesty]. They trample on virgin bashfulness with a sort of bravado, and glorying in their shame, become more audaciously lewd than men... But these poor ignorant wretches never had any modesty to lose, when they consigned themselves to infamy; for modesty is a virtue not a quality. No, they were only bashful, shame-faced innocents; and losing their innocence, their shame-facedness was rudely brushed off; a virtue would have left some vestiges in the mind, had it been sacrificed to passion, to make us respect the grand ruin.

Instead of worrying about bashfulness, women should strive to improve their understanding, and their wider compassion, and this will lead, via "purity of mind", to modesty. Dwelling on flirting and love will not have such happy results:

Those women who have most improved their reason must have the most modesty—though a dignified sedateness of deportment may have succeeded the playful, bewitching bashfulness of youth. To render chastity the virtue from which unsophisticated modesty will naturally flow, the attention should be called away from employments which only exercise the sensibility; and the heart made to beat time to humanity, rather than to throb with love. The woman who has dedicated a considerable portion of her time to pursuits purely intellectual, and whose affections have been exercised by humane plans of usefulness, must have more purity of mind, as a natural consequence, than the ignorant beings whose time and thoughts have been occupied by gay pleasures or schemes to conquer hearts.

She is clear that modesty does not lie in the actions one performs or the etiquette one adheres to:

The regulation of the behaviour is not modesty, though those who study rules of decorum are, in general, termed modest women. Make the heart clean, let it expand and feel for all that is human, instead of being narrowed by selfish passions; and let the mind frequently contemplate subjects that exercise the understanding, without heating the imagination, and artless modesty will give the finishing touches to the picture.

Chastity isn't a word used much now, except if you are Sonny and Cher picking a name for your daughter. In the Biblical sense it means virginity before marriage and monogamy within it. In effect, adhering to community norms. Mary distinguishes it from modesty.

As a sex, women are more chaste than men, and as modesty is the effect of chastity, they may deserve to have this virtue ascribed to them in rather an appropriated sense; yet, I must be allowed to add an hesitating if:—for I doubt whether chastity will produce modesty, though it may propriety of conduct, when it is merely a respect for the opinion of the world, and when coquetry and the lovelorn tales of novelists employ the thoughts. Nay, from experience and reason, I should be led to expect to meet with more modesty amongst men than women, simply because men exercise their understandings more than women.

Remember she wrote both Vindications before she went to Paris and met Gilbert Imlay. She is thought to have been a virgin up till that point, a subject I hope to discuss in a future post.

Also, it has not passed me by that this discussion of modesty bears some resemblance to the Muslim concept of hijab, too often understood only as dress restrictions for women, most specifically the headscarf, but in fact a statement of the necessity of modesty, applying equally to men and women. Again, something I may come back to, once Jane Austen and Lyndall Gordon and the Scandinavian traveller and all sorts of sculptural possibilities are out of the way.

Also, it has not passed me by that this discussion of modesty bears some resemblance to the Muslim concept of hijab, too often understood only as dress restrictions for women, most specifically the headscarf, but in fact a statement of the necessity of modesty, applying equally to men and women. Again, something I may come back to, once Jane Austen and Lyndall Gordon and the Scandinavian traveller and all sorts of sculptural possibilities are out of the way.

No comments:

Post a Comment