This is part of an intermittent series on

Mary Wollstonecraft's sons and daughters, mostly on Thursdays, unless more pressing and current projects come to light (such as the

Stoke Newington Literary Festival) or Blogger decides to take a holiday. Mary has a legacy, and while those who are now alive -- such as

Ayaan Hirsi Ali and

Amartya Sen -- may be vociferous in their praises, the women (and men) who read the

Vindications in the decades after her death were often more muted. Self-censorship is the better part of valour, apparently.

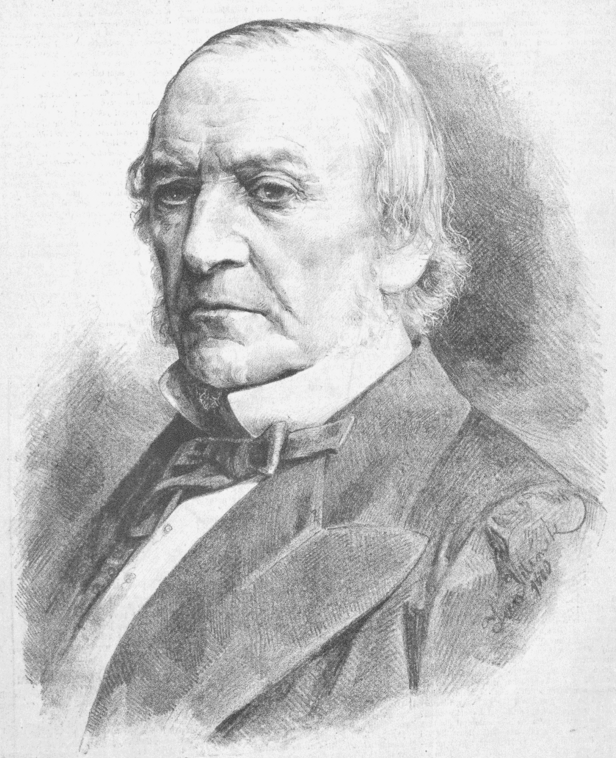

So, today, let us lift the veil on her lost son, William Gladstone, Victorian statesman, who, along with his arch-rival Disraeli, for decades set the tone for the leadership of the British Empire. Gladstone had begun life hoping to become a clergyman, but his father advised him to go into politics, which he did, starting as a High Tory and migrating via the Peelites to head of the Liberal Party. He was a reformer at heart, and fought for the extension of the (male) franchise and the secret ballot (which he won) and Home Rule for Ireland (which he did not, though he lessened the power of the Anglo-Irish landlords). It was on his watch that the

Elementary Education Act was passed, and this is where Mary Wollstonecraft comes into the story.

As I said before:

Gladstone repeatedly read and annotated Wollstonecraft while he was planning the structure of the state education system, but probably didn't quote her publicly, as she was persona non grata for a Victorian politician to be hobnobbing with. (I would love to be corrected on this: did Gladstone acknowledge his indebtedness to her in shaping his thoughts?)

This was an allusion to a book I had come across by serendipity last year. Time for a little more detail. Opposite the British Library I found a copy of

Gladstone and Women by Anna Isba (2006), with chapters on sisters, daughters, "fallen women" (he was big on those), mother, wife, queen (she was not so keen on him). Isba says, "As on many aspects of women's issues, what Gladstone thought of equal educational opportunities for both sexes is not entirely clear." I think it is fair to consider Mary Wollstonecraft first and foremost an educator, and

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman can be read as an educational treatise. We've previously looked at

her views on education, detailed in one of its final chapters, in which she argues for creating a national system that would bring both sexes and all classes together, side by side for at least the first few years. I had not known that Gladstone read her

magnum opus twice, "once in May 1849 and again in January 1864", adding marginalia. (The Elementary Education Act was passed in 1870, after many years of lobbying, notably from the

National Education League, which Joseph Chamberlain and other Dissenters spear-headed

. They wanted compulsory education for all children, without religious doctrine, which inevitably the Church of England opposed, via the National Educational Union.)

Now, I don't have access to Gladstone's copy of

Vindication -- yet. I have not yet been to

Gladstone's Library, formerly known as St Deiniol's, to see it for myself. (Another blogging coincidence: today is their Founder's Day.) I don't know if his copy has been scanned, marginalia and all. What I have to go on is Isba's work. She tells us:

Though he expressed himself uncertain of the merits of "this scheme of educating boys and girls together", Gladstone wrote in the margin that Wollstonecraft's section on co-education "on the whole I think...the best in the book and some hints in it are worth consideration". How much serious consideration he personally gave to questions of equal opportunity of education, let alond co-education, remains unclear.

One part of Gladstone's copy definitely has been scanned:

the flyleaf, on which he wrote his thoughts -- sort of a book review or

aide memoire.

A digital version of this page is hosted rather attractively by Gathering the Jewels, "the website for Welsh heritage and culture", a project sponsored by the National Library of Wales. I had found this some months previously, and was sure some expert must have transcribed the inscription, but thought I would try my hand at deciphering his, for the fun of it. I didn't get very far before I decided to call in the hivemind; I set up a simple Google Doc and put the word out on Twitter, and soon enough was joined by a paleographer from deepest France. We had an excellent time on GChat, with me saying things like "it's possible, but the letter after the J seems more rounded and "closed" than a u, doesn't it?" And eventually we got there, mostly. We appear to have been led astray by the devil, however: she said a certain squiggle was "Satan", and I went along with that tempting apple.

But, of course, Gladstone and Women includes that inscription, and Isba is presumably more familiar with the stateman's squiggles than most pharmacists are with those of their prescribing doctors. She transcribes that dubious word as "nature"; my error seems akin to listening to heavy metal backwards and finding Satan wherever you look for him. (The devil is in the details.) (Sorry, couldn't resist.) Gladstone's summary of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman thus reads:

The intention is good, and it contains many or some good things; but it aims by far too much at effacing in practical life distinctions which God, and nature his instrument, have made indelible.

There's an intriguing bit before that, which I will save for another time. But the point of this post is, the four-times prime minister and four-times chancellor of the exchequer read the work of Mary Wollstonecraft with respectful critical attention. Her thoughts on national education influenced those of William Gladstone, and, from him, the system that came into being shortly afterwards and whose legacy is still with us today.

[Small additions, e.g. glosses, historical context, bad puns, and images, the following day.]

Portrait of Gladstone by Jan Vilímek [Public domain]. The crepuscular glory of Gladstone's Library, by

David Long [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]. Both images via Wikimedia Commons.

.jpg)

.jpg)